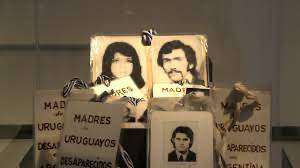

Next 18 December will mark the 30th anniversary of the adoption by the UN General Assembly (‘UNGA’) of the UN Declaration on the Protection of all Persons from Enforced Disappearance (‘Declaration’). This instrument formulates a series of principles that all States are expected to know and respect, in order to prevent and eradicate enforced disappearance. Thirty years after the adoption of the Declaration, regretfully the practice of enforced disappearance persists worldwide, as revealed by reports of expert bodies and NGOs. The challenge of eradicating this scourge remains thus pressing.

In this post I recall the principles of the Declaration and point to some problems concerning the implementation of these principles by States. Their dissemination among governments, NGOs and the general public could generate discussion as to how to fix such problems in the near future, which in turn may hopefully contribute to at least decrease the practice of enforced disappearance.

Definition of ‘enforced disappearance’

The preamble of the Declaration characterises an enforced disappearance as the act whereby “persons are arrested, detained or abducted against their will or otherwise deprived of their liberty by officials of different branches or levels of Government, or by organised groups or private individuals acting on behalf of, or with the support, direct or indirect, consent or acquiescence of the Government, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate or whereabouts of the persons concerned or a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of their liberty, which places such persons outside the protection of the law”. This definition has proven to be universally acceptable, as evidenced by its almost verbatim reproduction in article 2 of the Inter-American Convention on the Forced Disappearance of Persons (1994), in article 2 of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance (2010), and in the African Commission Human and Peoples’ Rights Guidelines on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance in Africa (2022).

The definition of enforced disappearance quoted above does not encompass acts tantamount to enforced disappearance carried out by a non-State actor not acting on behalf of, or with the support or the consent of the State (the definitions formulated in the other three above-referred instruments neither). Hence, the deprivation of liberty of a person by terrorist groups or by insurgents, followed by a refusal to disclose the fate of the person deprived of liberty, will not generate the international responsibility of the State in whose jurisdiction the act has taken place. This is without prejudice to any issue of individual criminal responsibility. Thus, for example, the definition of enforced disappearance under the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court does also cover conduct performed by a person belonging to, or acting with the authorisation, support or acquiescence of “a political organisation” (article 7(2)(i)). Despite the narrow scope of the Declaration’s definition, the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (‘Working Group’) has recently developed the practice to also document instances of acts tantamount to enforced disappearance, provided that the non-State actor concerned exercise effective control over the territory in which the act is taking place.

Principles of the Declaration

Acts of enforced disappearance may breach multiple human rights at once: the right to recognition as a person before the law; the right to liberty and security; the right not to be subjected to torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; and the right to life. This is why enforced disappearance is deemed particularly offensive to human dignity (article 1).

The Declaration is based on two principles: the prohibition of enforced disappearance and the principle of international cooperation in the prevention and eradication of this scourge (article 2). The mere formulation of both principles would be meaningless if States were not required to take effective measures to attain the objectives of the Declaration (article 3). The prohibition of enforced disappearance would also be meaningless if States were allowed to derogate therefrom; this is why enforced disappearance cannot be justified under any circumstance, such as war or any other public emergency (article 7).

Many of such measures must be adopted in the area of criminal law. To begin with, States are required to criminalise enforced disappearance (article 4), to provide for “appropriate penalties” therefor (idem), and to stipulate the irrelevance of superior orders as a ground for excluding criminal responsibility (article 6). Next, they are required to comply with the principle of aut dedere aut iudicare. State differently, States must investigate acts of enforced disappearance and prosecute the persons allegedly responsible when the facts disclosed by the investigation so warrant, unless said persons are extradited to another State willing to exercise its criminal jurisdiction (article 14). Moreover, the prosecution of persons allegedly responsible for enforced disappearance must be carried out by ordinary courts, not by special courts or by military courts (article 16). States are also required to treat the crime of enforced disappearance as a continuing offence -the crime is deemed to persist as long as the perpetrators continue to conceal the whereabouts and the fate of the victim- (article 17). Statutes of limitations, if applicable, should be proportionate to the extreme gravity of this crime (article 17). In a similar vein, States are urged not to enact amnesty laws for enforced disappearance (article 18). Furthermore, although according to this provision States appear to retain the power to grant pardons of sentence for this crime, the Working Group has clarified that that they are prohibited, because they would run against the obligation to punish enforced disappearance (see Report of the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances on standards and public policies for an effective investigation of enforced disappearances, para. 27 et seq.)

Beyond the area of criminal law, the Declaration provides for the principle of non-refoulement (article 8), likewise international refugee law and treaties against torture. By virtue of this principle, no one shall be expelled, returned or extradited to a State where there are substantial reasons to believe that he or she may be victim of enforced disappearance.

Furthermore, domestic laws ought to provide for the right to a prompt and effective judicial remedy to determine the whereabouts or state of health of persons deprived of their liberty or the identification of the authority ordering or carrying out the deprivation of liberty (article 9). In the same vein, States are required to hold detainees in official places of detention and to brought them before a judge promptly after detention, to promptly inform family members and counsel of the detainee of the detention, and to maintain up-to-date official registers of detainees in places of detention (article 10). These measures are intended to prevent acts of enforced disappearance.

Other than that, the Declaration proclaims the right of victims to reparations; not only in favour of the direct victims, but also of the victims’ dependants in the event of the death of the former as a consequence of the enforced disappearance (article 19).

Finally yet importantly, States are called upon to prevent and eradicate the abduction of children of parents victims of enforced disappearance and of those born during their mother’s enforced disappearance. They are expected to search, identify, and restitute the children to their families of origin, as well as to criminalise the abduction of children of parents victims of enforced disappearance or of those born during their mother’s enforced disappearance (article 20).

Problems in the implementation of the principles of the Declaration

In this regard it is worth examining the practice of the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances. The Working Group was created in 1980 by the now extinct UN Human Rights Commission (Resolution 20 (XXXVI)) and is composed of five independent experts. The Working Group assists relatives of persons subjected to enforced disappearance in elucidating their whereabouts, by serving as a communication channel between the persons or organisations reporting the disappearance and the State concerned. To this effect, the Working Group: receives, analyses and transmits to States reports of enforced disappearances received from family members or representatives of victims; requests States to investigate allegations of enforced disappearance and to inform the Working Group of the outcomes; and assists States in overcoming obstacles to the implementation of the Declaration.

In the report entitled “Thirtieth anniversary of the Declaration on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance“, the Working Group examines the contribution of the Declaration to the development of international and domestic case law, the problems faced in the implementation of the Declaration, and the lessons learned so far.

As far as the problems arisen from the implementation of the Declaration, the Working Group makes a number of observations, including but not limited to the following ones.

First, a number of States do not criminalise enforced disappearance as a separate crime, in the belief that conduct already criminalised in their jurisdiction -such as abduction- would be sufficient to meet the obligation to criminalise enforced disappearance. Other States do criminalise enforced disappearance as a separate crime, but their definitions of the crime does not match the definition formulated in the Declaration, with the consequence of creating legal loopholes. Finally in this regard, the Working Group point out that the penalties for enforced disappearance provided for some domestic laws are not proportionate to the extreme seriousness of the crime. It is not clear whether the Working Group means the imposition of penalties other than imprisonment, the imposition of short terms of imprisonment, or both alternatives.

Furthermore, the Working Group reports that certain State policies and agreements between States are aimed to circumvent or even breach the principle of non-refoulement, leaving persons at risk of enforced disappearance in the country of destiny.

The Working Group has also detected problems in the implementation of the fundamental guarantees proclaimed in articles 9-12 of the Declaration for individuals deprived of their liberty. Thus, for example, the anti-terrorism laws of several States significantly limit or suspend altogether such guarantees, by failing to establish procedures to exercise the right to a prompt and effective judicial remedy to determine the whereabouts of persons deprived of their liberty in all places of detention, and by failing to preserve up-to-date official registers of detainees.

Moreover, numerous obstacles have been encountered in relation to the search and investigation of enforced disappearance, such as: the elapsing of long time before a search begins, making the prosecution of alleged offenders even more difficult; the failure to preserve mass graves; intimidation or harassment of relatives of the disappeared, their legal representatives, or witnesses of enforced disappearance; and the nonexistence of lists of victims.

Furthermore, the Working Group reports that the prosecution of persons allegedly responsible for enforced disappearance has taken place before special or military tribunals in some States, contrary to the provisions of the Declaration. Besides, there have been reports of amnesty laws in favour of persons allegedly responsible for enforced disappearance.

Last but not least, it appears that reparations for victims of enforced disappearance are often not approached in a holistic manner, that is, as encompassing compensation, rehabilitation, restitution, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition.

Conclusion

Thirty years after the adoption of the Declaration, the practice of enforced disappearance has not been eradicated. Even worse, one may wonder whether the frequency of its occurrence has decreased worldwide.

States are therefore strongly advised to address the above-referred problems concerning the implementation of the Declaration. They may take stock of the recommendations of the Working Group to that effect (see here, paras. 77 et seq.) or they may adopt other effective measures. In any case, States should act now. Victims of enforced disappearance cannot wait.