The information that I bring here is unprecedented and very important, so Maastricht Blog on Transitional Justice deserves to be the first of all to report it.

As already reported by Prof. Flávio de Leão Bastos Pereira in January, 2022, a judicial process is underway in Sao Paulo-Brazil that aims to transform the former Doi-Codi facilities into a memorial. This memorial has two main purposes: to pay tribute to the thousands of tortured people and the dozens murdered by that agency between 1969 and 1983; to promote a better understanding of how the largest and most important center of repression of the Brazilian civil-military dictatorship functioned and was structured.

Created in 1969 from a consortium formed between the Government of the State of Sao Paulo, the Army and large companies, Doi-Codi was initially called Operação Bandeirante. It was installed on the premises of the Army’s 2nd Mechanized Reconnaissance Squadron, just 1km away from where it was later transferred, at Rua Tutoia, 921, occupying half of the 36th Police Station and an annex building at the back of the land. Understanding the importance of this place, in addition to its undoubted historical relevance, but also material and as an element of documentary evidence of the commission of felonies by the Brazilian State, it has been part of my work at the Historic Heritage Preservation Unit of the Secretary of Culture of the State of São Paulo since 2010.

In that year, the Council for the Defense of Historical, Artistic, Archaeological and Tourist Heritage of the State of Sao Paulo (Condephaat) was required to list as cultural heritage such buildings, considering “their historical importance and relevant didactic role that the aforementioned building has for generations of young Brazilians, who ignore the atrocities committed there, the listing will guarantee the preservation of this important physical document of our recent history” (SEIXAS apud NEVES, 2018). The request was presented by Ivan Akselrud Seixas – arrested at Doi-Codi in 1971 at the age of 16 along with his father Joaquim Seixas, murdered under torture days later. Five human rights organizations endorsed his request, including the State Council Defense of Human Rights (Condepe), state agency linked to the Secretariat of Justice and Citizenship. Provided for in the state constitution, Condepe’s main purpose is to “investigate human rights violations in the territory of the state of São Paulo” (CONDEPE, https://justica.sp.gov.br/index.php/servicos/condepe/).

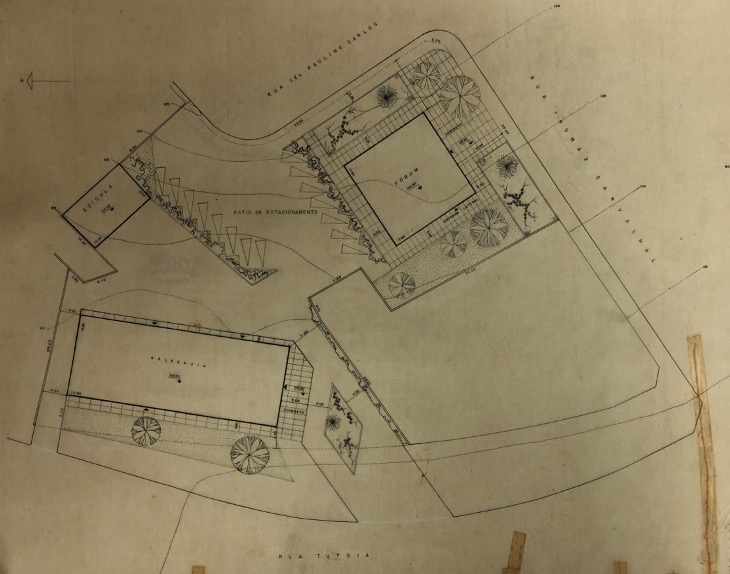

From this request, initial technical reports prepared between September and December 2010 pointed to the historical importance of the place, consisting of four buildings, a patio and covered garage, with two possible entrances: one through Rua Tutoia, leading to the police station, and another along the perpendicular street – Tomás de Carvalhal. There were no outstanding or notable architectural values there – they were mass-produced buildings, probably in the 1960s, due to their stylistic characteristics. Like these buildings, there were many other police stations throughout the state of Sao Paulo. Two other buildings were out of tune: one resembled a residence and the other had exposed bricks and a garage on the ground floor, surrounded by a wall with two guardhouses, a typical feature of military installations.

In May 2012, Condephaat decided to preliminarily protect the building, guaranteeing the preservation of the property until the end of the technical studies and final decision of the Council. Between May 2012 and October 2013, the deepening of the studies allowed us to understand the dynamics of the Doi-Codi operation in each of the buildings. It also allowed us to understand how the military occupation of government buildings originally destined for civilian use took place. Based on research, very important documents were found:

- Decree 36.628/1960, which permitted the expropriation of three lands for the construction of the police station, and the respective transcripts of the land registry office. The Decree confirms the thesis of serial construction policy, since several other expropriations were authorized in different cities of the State of Sao Paulo;

- Two administrative processes that deal with the agreement for the transfer of part of the land from the State Public Security Secretariat to the Second Army Command;

- Aerial photographs from 1958, 1962, 1968, 1973 and 1977 that allowed identifying the evolution of construction. Initially, the police station and its annex building. In 1960, buildings in reinforced concrete, with external coating made of ceramic tiles, two floors, longitudinal and wide windows. Between 1968 and 1973, the common residence, with symmetrical sides and ceramic roof, with a facade protected only by painting, and a brick building built on structures above ground level. These constructions, therefore, were constructed by the Army and therefore were different from the first ones.

Based on these documents, inspections were carried out with people who were kidnapped by Doi-Codi between 1969 and 1975 and who reported where they were detained, where they were interrogated and tortured, where they entered the buildings and what they were able to recognize from this visit. In Brazil, it was the first time that a heritage preservation agency and former political prisoners worked in partnership for the recognition and preservation of a building related to the forces of governmental repression.

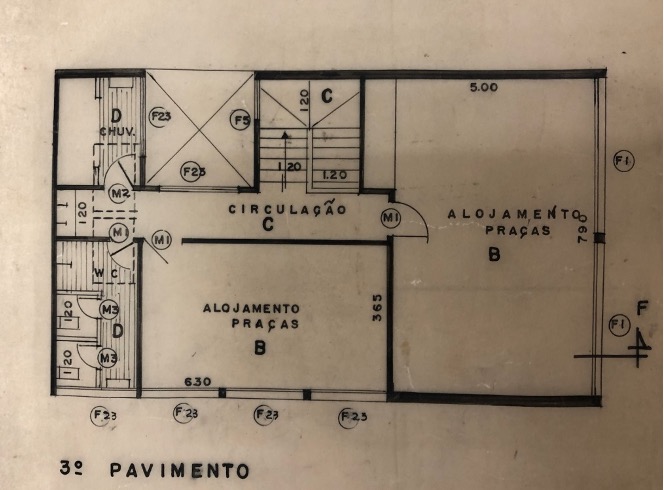

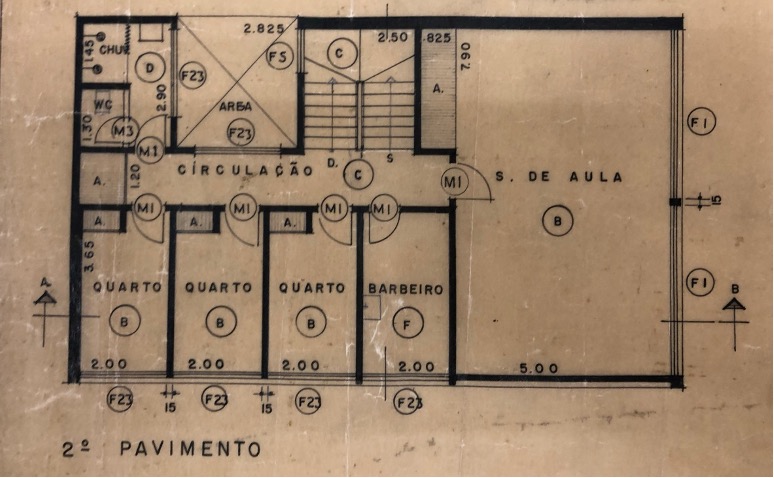

However, we did not find the original architectural plans for the buildings. The administrative processes indicated that the Army did not present the plans for the constructions that it carried out from 1969, but we believe that they exist. The buildings built to house the police station in 1960 should have blueprints since they were included in the State Government’s Action Plan, which provided for the construction of hundreds of public facilities. However, they were not located at the time of the study, which led us to create an alternative simple plan to the building. This plan helped the ex-prisoners to identify where they were interrogated and tortured; and it allowed the technical team of the Historic Heritage Preservation Unit (UPPH) to choose different degrees of preservation for the buildings, considering the use and the value of material evidence.

Ten years after the beginning of the studies, UPPH learned that the collection of the Department of Public Works, which was responsible for the Action Plan, had been incorporated into the Public Archive of the State of Sao Paulo after being inaccessible for least two decades. In consultation with the Cartography Center, we requested a search of the collection and finally the plans were located thanks to the commitment of the Archive employees involved in the search, bringing us joy and the possibility of furthering archaeological and architectural research to support the creation of the memorial.

Three initial aspects of these documents draw attention:

One, the annex building was originally designed to be a training and housing unit, whose character was perverted and transformed into a place of interrogation, torture and murder;

Two, the existence of a barber shop on the first floor confirms the testimony of Ivan Seixas, who reported that it was in that room that his father was tortured in the Dragon Chair (a kind of electric chair), because he remembered the sink installed there. The sink was provided for in the original plan;

Three, the last aspect resolves a doubt as to why only two buildings were built in the early 1960s, leaving the land empty. With access to the original project, the police station and the annex would be used as a kind of training center, containing two classrooms, a barber shop and 5 bedrooms with beds. In the area where the Army built its intelligence sector and accommodation, the construction of a Court was originally planned.

Thus, in that place where thousands of people were tortured and dozens were murdered, the principles of Justice passed away, distorting its initial purpose. As Flávio de Leão Bastos Pereira reported here, it was only in 2021 that Justice really filled in that space, on the occasion of the conciliation hearing between the State and the Public Ministry. It was the first time that Justice entered Doi-Codi, but it was not the first time that it was designed for that space. Education will also have space, not to train the Police, but to transform it.

These original documents are still under analysis and will serve as a basis for archaeological research scheduled to begin in July 2022 as part of a project to create and build a memorial, transforming the space into a place of memory and consciousness. However, they already show the importance of public records and of scientific research for serving transitional justice, which is moving slowly in Brazil.

Deborah Neves is Ph.D. in History, specialized in cultural heritage and sites of difficult memories. Historian at Historical Heritage Preservation Unit, Government of the Sao Paulo State, Brazil