Author: Andrea Trigoso

Disponible en español

In 2001 Peru entered a post-dictatorship and post-armed conflict transitional period. Since then, various transitional justice (TJ) mechanisms have been established to address the pillars of truth, justice, reparation, and non-repetition required by the universal model of TJ. Nevertheless, after 20 years the TJ agenda receives little attention, as does the assessment of whether the TJ period has ended or if there are still pending challenges. This post briefly summarizes the current state of TJ in Peru and mentions some of the pending challenges for each TJ pillar.

1. The armed conflict in Peru

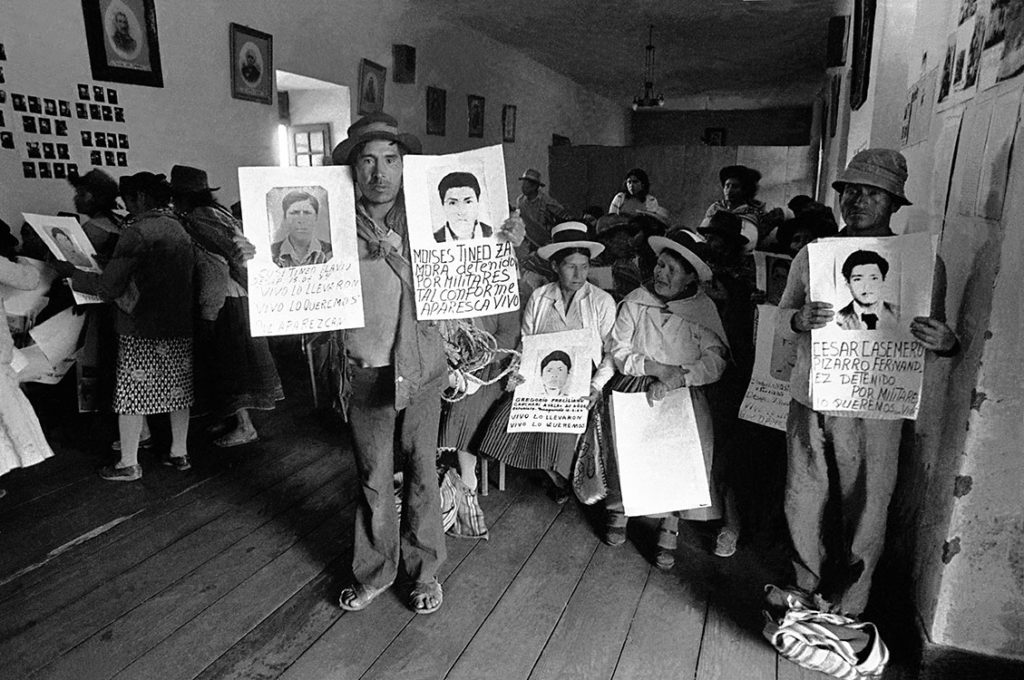

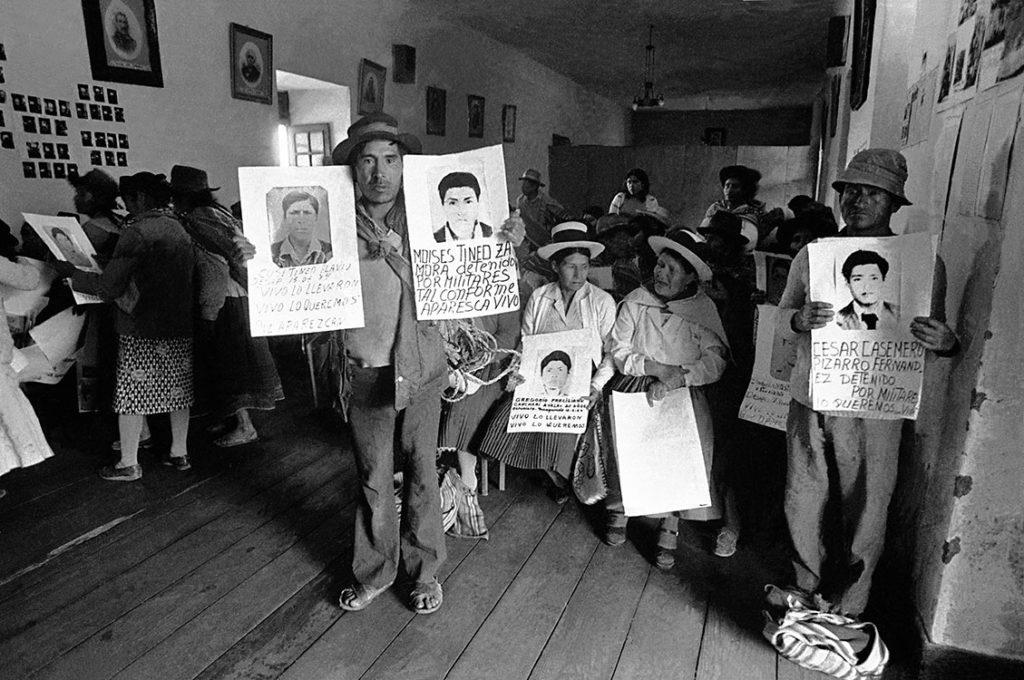

Photo Abilio Arroyo- Caretas

During the closing decades of the last century, Peru went through an internal armed conflict and was subject to an authoritarian regime. According to the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), the armed conflict began in 1980 with the public burning of the electoral amphorae in the village of Chuschis, perpetrated by the terrorist organization Sendero Luminoso – Shining Path (SL), and it lasted until 2000. In the last decade of that period, Alberto Fujimori, who was democratically elected as president in 1990, perpetrated a coup on April 5, 1992. With the support of the armed forces, Fujimori dissolved the Congress and established an antidemocratic regime that ended in November 2000, when he resigned by fax from Brunei, where he was attending the APEC summit.

It is worth mentioning that prior to the internal armed conflict, Peru had a military dictatorship, which had been established in 1968. The military junta appointed General Juan Velasco Alvarado as de facto president, who was himself deposed in 1975, after another coup. The new de facto president, General Francisco Morales Bermúdez installed a Constituent Assembly in 1979 and called for democratic elections in 1980.

Consequently, during the period of transition to a democratic government, an armed conflict started in Peru. Thus, the period in which mechanisms to deal with human rights violations committed during the military dictatorship should have been established, Peru had to face the uprising of terrorist violence, with young and weak democratic institutions, and an almost non-existent rule of law.

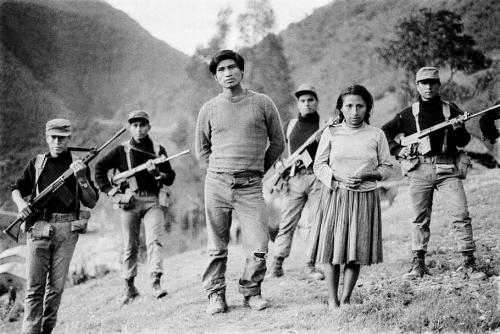

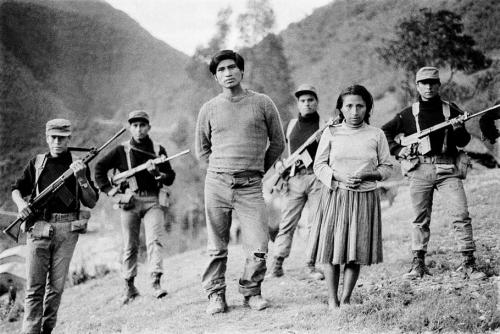

During the armed conflict, there were two terrorist organizations responsible for the attacks and mass atrocities. SL led by Abimael Guzmán, a group to which the TRC attributes the highest number of deaths (54%), and the Revolutionary Movement Tupac Amaru (MRTA), to whom the TRC attributes 1.5% of deaths. The latter group extinguished after the Chavín de Huántar operation, in which the armed forces broke into the Japanese Embassy in Lima to rescue the hostages taken by the MRTA.

Shining Path, on the other hand, has not ceased to operate in Peru. After the capture of Abimael Guzmán in 1992, and the consequent dismantling of a large part of the organization, SL continues to operate in the zone of the Valley of the rivers Apurímac, Ene, and Mantaro (VRAEM). This is despite the capture of other SL leaders such as Oscar Ramírez Durand (a.k.a comrade Feliciano) or Jorge Quispe Palomino (a.k.a comrade Jose). However, the current group is divorced from the initial ideology of Abimael Guzmán (pensamiento Gonzalo) and survives through illegal activities such as drug trafficking, extortion, and murders.

Furthermore, the armed forces and the police were also responsible for serious human rights violations. State agents, self-defense committees, and paramilitary groups were responsible for 37% of deaths and disappearances reported to the TRC. Emblematic cases that illustrate this period are the Cabitos military base, and the Frontón prison before the Fujimori dictatorship, and the cases of Barrios Altos and La Cantuta, during the Fujimori dictatorship.

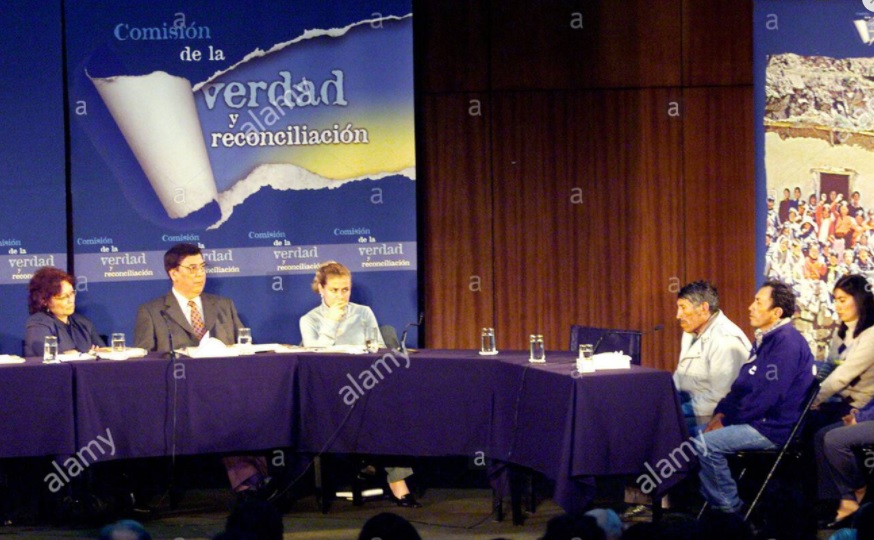

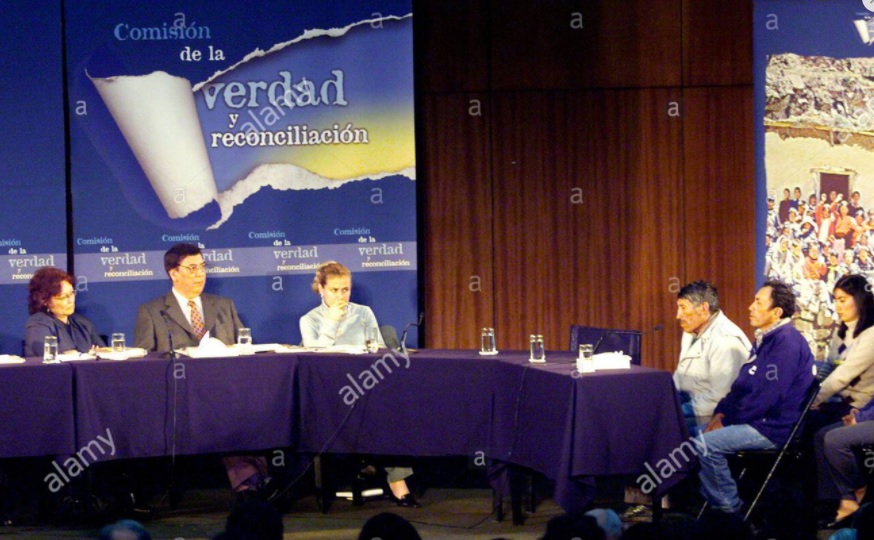

2. Truth, justice, reparations

After the end of the authoritarian regime, Peru started a period of transitional justice, which seems to be still ongoing. The transitional government of Valentín Paniagua created the TRC in June 2001, with the task of establishing the facts about the terrorist violence and the serious human rights violations that occurred in the preceding decades. The mandate of the Commission included the clarification of the political, social, and cultural conditions that permitted the conflict; assist the judiciary to establish the truth about the crimes committed by the terrorist organizations and State agents, as well as to identify alleged responsibilities; submit proposals for reparation, recommendations for institutional reforms, and the establishment of monitoring mechanisms for the recommendations. In August 2003, the final report of the TRC was presented. It gathered the testimonies of 17.000 victims and calculated the loss of 69.000 lives during the conflict. In addition, its recommendations on reparations fostered the comprehensive reparations program, and the findings on human rights violations and terrorist acts contributed to the prosecution of these cases.

Moreover, the judicial bodies have also made efforts towards the investigation and prosecution of terrorist acts and serious human rights violations. The judiciary created the National Criminal Chamber and endowed it with jurisdiction for cases of terrorism and serious human rights violations. The Office of the Public Prosecutor also created a specialized subsystem for the same type of crimes. Within the framework of these subsystems the SL leader, Abimael Guzmán, and the SL’s leadership were retried in 2005. The new trial followed a decision of the Constitutional Court that declared the previous trial null and void, because it was conducted in the military jurisdiction, in summary manner, and with “faceless judges.” In 2006, Abimael Guzmán was sentenced to life imprisonment along with other SL leaders, who never apologized to the victims.

The human rights violations perpetrated by State agents have also been prosecuted within the aforementioned judicial system: illustrated in the cases of Accomarca, Cabitos, Barrios Altos, and la Cantuta. Alberto Fujimori was also tried for the facts that concern these last two cases, and he was sentenced to 25 years in prison. Nevertheless, the prosecution of these cases has presented a series of technical challenges (related to the evidence and principle of legality), as well as obstructions of political nature. Proof of this is that emblematic cases such as Accomarca and Cabitos were sentenced and reached final judgments only 31 and 35 years after the events occurred (with many defendants removed from the process for health or other reasons), and that there are cases from that period that are still in trial, or even remain at the investigation stage (see cases Manta y Vilca, Fronton, and Forced Sterilizations), because they are investigating mass crimes committed by high-ranking military personnel and political leaders.

Following the TJ framework, Peru has gradually implemented a comprehensive reparations plan (CRP) recommended by the TRC. In 2005, the Congress enacted a law creating the CRP that was composed of the following 6 programs: restitution of citizens’ rights, reparations in education, reparations in health, collective reparations, symbolic reparations, and facilitation for housing access. Additionally, this law and its regulations established that the High Level Multisectoral Commission (CMAN), and the Reparations Council (RC) -in charge of the registry of victims – would be in charge of the implementation of the CRP.

The aforementioned normative framework for reparations considers the relatives of the disappeared or killed persons, displaced persons, persons who were arbitrarily detained, tortured victims, victims of rape, kidnapped persons, members of the armed forces, the national police, self-defense committees, and civil authorities wounded or injured in actions that violated their human rights as beneficiaries of the CRP. Likewise, indirect victims are also beneficiaries of the CRP, considered as such: children who were the product of rape, minors who were part of self-defense committees, people unduly accused of terrorism, and people who were undocumented because of the conflict. Peasants and native communities, and other small rural villages affected by the violence and groups of organizations of non-returning displaced persons are also beneficiaries of the CRP as collective victims. The exception to these categories are former members of the terrorist organizations, even if they suffered human rights violations, and victims who have already received reparations for other decisions or State policies.

The report on reparations in Peru from the Queen’s University of Belfast indicated that until April 2018 there were 226.727 people registered in the single registry for victims; 5.712 communities and rural villages, and 127 organized groups of non-returnees were registered for collective reparations. Of this total, the CMAN has given reparations to 1.852 (32.5%) rural villages and communities in fifteen departments. Additionally, the report indicates that individual financial reparations were granted to 98.132 beneficiaries; 12.082 people were registered in the Special Registry of Beneficiaries of Reparations in Education; 139.296 beneficiaries of the health reparations program joined the National Comprehensive Health Insurance. The report also points out that as symbolic reparations, the Place of Memory, Tolerance and Social Inclusion (LUM) was created, which is a space for pedagogical and cultural commemoration, and the Monument “the eye that cries” was built as an initiative from the civil society. Finally, the report mentions that the Ombudsman’s Office registered around 2.000 victims of enforced disappearance, which has allowed their declaration of absence and access to related civil rights for their family members.

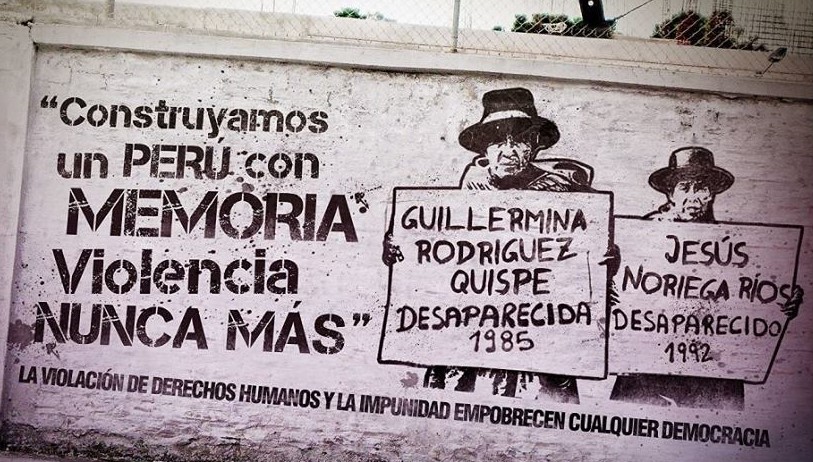

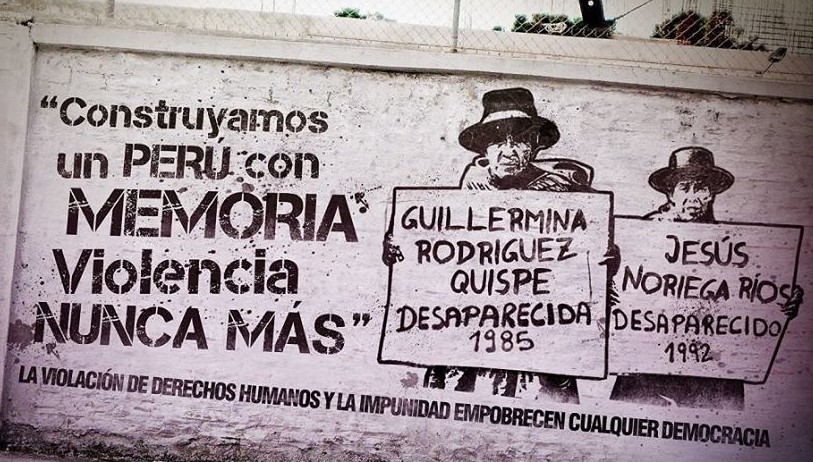

Despite the progress in reparations, there are still many challenges Peru must face. These include the many provisions and registries established for the victims, because they are confusing and mutually exclusive, which makes it difficult for victims to benefit from the reparations programs. Other challenges to execute the reparations program include the lack of coordination between the State entities, the misperception of reparations as social programs, the failure to institutionalize the budget for reparations, the lack of symbolic reparations that include public expressions, and the lack of political will to carry them out.

3. Guarantees of non-repetition

Regarding institutional reform, the Peruvian State has had limited activity. An illustrative example of this is the TRC recommendation for strengthening the independence of the administration of justice that entailed the establishment of an independent system for the appointment, evaluation, and sanction of magistrates (judges and prosecutors), and the reestablishment of the judicial career. An effort in this regard was made with the enactment of the law for the judicial career. However, no structural change or vetting system was proposed, and a large number of provisional magistrates continued to be appointed. The more visible impact of this failure in the institutional reform of the judiciary happened in 2018, when a systematic corruption web involving judges and prosecutors of the highest level, and members of the National Council of the Magistracy (CNM), the body that evaluates and appoints magistrates, was discovered to be appointing magistrates through unlawful means. After this finding, the CNM was dissolved and a National Board of Justice was created to investigate these events, remove the magistrates involved, and propose reforms for the appointment and evaluation of magistrates.

In addition, the TRC recommended measures for the armed forces and the police, which involved training in human rights, the introduction of civilian control in the intelligence services, and the definition of the police as a non-militarized civilian institution in the constitution. Even though there have been efforts to improve the human rights training for both institutions, they have not reviewed their protocols to ensure compliance with human rights standards, no civil controls have been introduced to the armed forces, and the constitutional definition of the police has not changed. The consequences of this lack of reform are evident in the mismanagement of public order crisis, especially when facing protests, which have left citizens dead and others injured in recent years (see protests of November 14, 2020 and the agricultural strike of December 2020)

Furthermore, the TRC recommendation to strengthen the presence of the State throughout the territory, especially in the most neglected and affected areas by the conflict, has been hardly implemented. The causes of the conflict, according to the TRC, are related to the absence of the State and exclusion in the political, social, and economic representation of a sector of the population. This link was so strong that the TRC found there was a relationship between the situation of poverty and social exclusion and the probability of being a victim of armed violence. After twenty years, these structures have not changed, and this scenario does not guarantee the non-repetition of the violent past.

4. A final remark

Twenty-one years after the armed conflict ended, is clear that the TJ period in Peru has not yet finished, and there is still a lot to do for each TJ pillar. In the current state of affairs, the reconstruction of the social tissue and the re-founding of a social pact that generates trust between citizens and in the Peruvian State institutions is a distant but urgent aspiration that could generate reconciliation in the country. Therefore, the introduction of a TJ agenda in the public policies is a task that cannot be further postponed by the Peruvian government.

PS. Some of the pictures were taken from Yuyanapaq, a graphic account of the conflict. It can be visited here